- Home

- Rosemary Zibart

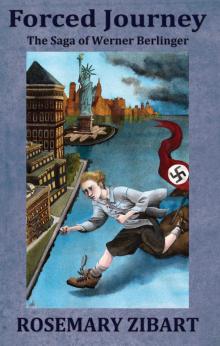

Forced Journey

Forced Journey Read online

Forced Journey:

The Saga of Werner Berlinger

ISBN: 9781932926934

Copyright © 2013 by Rosemary Zibart

Cover Illustration: Jeanne Bowman

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012952632

Printed in the United States of America.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return it and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without written permission of the publisher, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

Kinkajou Press is the young adult imprint of Artemesia Publishing

Kinkajou Press

9 Mockingbird Hill Rd

Tijeras, New Mexico 87059

[email protected]

www.kinkajoupress.com

FAR and AWAY

Forced Journey:

The Saga of

Werner Berlinger

by

Rosemary Zibart

Kinkajou Press

Albuquerque, New Mexico

www.kinkajoupress.com

Dedication

To Sister Sandra Smithson with love and appreciation.

To all the generations of children and to every child who has made that journey to find a new life and a safe home.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Epilogue

Author’s Note

About the Author

Foreword

It is a fact that approximately 1400 unaccompanied children came to the United States during the years 1934 to 1941. These children from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia were fleeing the Nazi regime. It is also a fact that many of these children became teachers, lawyers, doctors, engineers. One even became a rock star and another a Nobel Prize winner. What is little known is how these children reacted to being forced to leave their parents and family behind and to grow up in the United States, in many cases never to see one or both parents again. On the one hand, there was little that they could do to control their lives until they reached America’s shores On the other hand, once they had arrived here, they were pretty much on their own and that’s the basis for the fascinating tale spun by Rosemary Zibart in Forced Journey.

It is a challenging task, considering the range of ages and backgrounds of these young boys and girls, to distill their stories into the saga of Werner Berlinger, but Ms. Zibart has done so with empathy and understanding. It is not only an interesting read but there were many times in the story when I felt that what happened to Werner was what had happened to me.

Henry Frankel

President

One Thousand Children

“What you standing there gawking for?” A rough-looking young man with dirty blond hair spoke to Werner. The boy had paused a moment on the edge of town to gaze at a sign with an arrow: Hamburg, 64 kilometers. Then he’d become stuck on the spot. Scared. Afraid to take the first step and leave behind everything he knew and cared about.

“Better get moving, if you want to get somewhere before dark,” the fellow declared loudly. His clothes were as shabby as Werner’s, but warmer. He looked several years older, 16 or 17 at least, and much sturdier, a farm worker, perhaps. He started walking with long strides. Werner fell in beside him, trying to keep up.

“I call myself Gunther,” the fellow said, glad to have a traveling companion. “You know why there’s so many people on the road, don’t ya?”

Werner glanced around – the road was filled with people, mostly men, traveling in both directions.

“It’s War again,” declared Gunther. “That’s what it is.” He explained how he had heard on the radio that Germany had marched into Poland the day before, September 1, 1939. It had been a big success for the Nazis, he claimed. They’d flattened the Polish military.

“Those poor Polacks didn’t have a chance,” snorted the young man. “German soldiers are the best in the world, ain’t they?” Werner didn’t respond, but the guy didn’t seem to care.

“I’m heading to Hamburg myself to sign up as a soldier,” Gunther announced proudly. “My father don’t want me in the army. And Mother, she cried buckets. But it’s my life, ain’t it? And I’m no sissy.” He puffed out his chest and showed off his big arm muscles.

He didn’t ask the boy’s name and Werner didn’t volunteer it. He knew that he needed to be careful. If Gunther suspected he was Jewish, what might he do? Somebody so gung-ho for the German army could be dangerous. Father had warned, “Speak to as few people as possible.” Werner knew he was far safer on his own. So he was glad when Gunther found a more talkative young man and moved on.

Still, Gunther had gotten Werner moving and had set a fast pace. He was grateful for that. He had never traveled so far on his own. Every step carried him further from Father and his sister Bettina. His heavy boots were covered with mud, weighing them down and scraping his sockless feet raw. But he had to travel 64 kilometers in just three days. Then go even further – a ship, an ocean.…

At least Werner had a goal - get a foothold in America; a place to live, a home. Then Father had promised that he and Werner’s little sister would follow. This dimly burning ember of hope lit the boy’s path.…

Chapter One

“Werner, Werner Berlinger,” called Frau Schutz, matron of the orphanage.

“Uh oh,” Werner muttered to his friends.

It was late August. Rain had fallen for three straight days. The grey skies and chill in the air meant winter was not far off. Their bones ached from being inside all day and doing nothing. The boys had lapped up some thin gruel for breakfast. Then they had started playing checkers, with Werner winning as usual.

He wondered why Frau Schutz was calling his name. Was it because the night before he had snuck into the kitchen? Had someone snitched on him? He glanced around at his buddies, Victor, Sammel, Lutz and Mandel. Not one of them, surely.

Punishment at that orphanage was no joke. Frau Schutz made the children stand in a dark closet for hours or miss dinner. Missing out on food was worse than standing in the dark. Though even when they ate, it wasn’t much. Some watery soup and a little stale crummy bread, the kind the baker throws out if he can’t sell it.

Germany’s ruler, Adolf Hitler, had made his opinion clear. The more Jewish orphans (or sick or blind or aged or handicapped people) that starved to death, the better. So children in the orphanage were hungry all the time. Werner didn’t remember one day or one hour of one day when his stomach wasn’t growling. Often he got in trouble for stealing food – a piece of wormy cheese or fatty meat. Not worth stealing unless you’re starving.

He strolled over to Frau Schutz, trying to seem bold but expecting the worse. She surprised him. “Your father has written,” she said. “He instructs me to send you home.”

Werner’s mouth dropped open. He stared at her like a little kid, not a scrawny twelve year old. Home? Home? He was finally going home?

He glanced down the hallway at his gang of friends. Most kids at the orphanage didn’t have a parent but he did. And he had wanted – dreamed – of this news for a whole year.

“It is good your father wants you home, Werner,” Frau Schutz said. “You know the way, don’t you?”

He nodded. She wasn’t a bad person, he thought, just worn out, like a coin that’s been passed around too long. She didn’t like to punish the boys for stealing food, but there wasn’t enough for everyone and no child could get extra.

Werner stumbled down the hall, barely glancing at his friends. Still, they followed as he entered the long narrow room where their cots stood in a row. He knelt and reached underneath for the small wooden box with his things. Hands trembling, he took out the contents – a pencil, a little notebook and a precious photograph of his mother. Her soft round face and gentle eyes smiled up at him as always. The picture was smudged from the many tears that had splashed on the fading print in the years since she had died. He carefully put the picture in his pocket, then dumped the other stuff and a few clothes into a worn knapsack

“Ya going some place?” asked Lutz Chaimen in a squeaky voice. Just a little guy, he wanted to go too.

“Home,” Werner muttered, without looking up. He didn’t want to see the envy in the small boy’s eyes.

A minute later, ready to leave, he gave Lutz a squeeze, feeling the sharp bones beneath his skin. Victor, Sammel and Mandel were closer to his age, so he just nodded to them, not sure what to say. The boys had shared so many moments haunted by hunger and loneliness, they were like brothers in a ghost family.

“You’re not gonna finish the game?” Lutz trailed him down the dim hallway to the heavy front door.

“Nah, not today.” Werner paused and reached deep into his pocket. Months ago, he had discovered a large green and black marble in the dirt at the corner of the playground. He hadn’t told a soul, fearing it would be stolen. Now he handed the marble to Lutz, glad to see a smile flash across the youngster’s face.

A few minutes later, he was running down the road away from the orphanage. He didn’t glance back, but murmured a quick prayer. Please, God, please, help Lutz and the other boys get out too.

Then he recalled how he had gotten to that dismal place.

Chapter Two

It was a year ago and he was simply walking home. But they had spied him from across the street, a gang of troublemakers – the Hitler Jugend – teenage boys who tried to act as stupid and mean as adult Nazis. Often they had chased Werner down the street. Usually he outraced them, but not that day.

“Hey, big nose,” said a young tough, twice as a big as Werner. The sturdy blond boy twisted Werner’s arm while pushing a piece of chalk into his other hand.

“Write on the sidewalk,” he commanded, “I am an ugly Jew-boy.” Werner’s hand shook so much the scrawl was barely readable. Still, the boys in brown uniforms howled with laughter. Werner slinked home, hot with shame.

That night he wet the bed like a baby. It wasn’t the first time he had woken up with sheets damp and smelling of pee. His father said nothing in the morning. But while helping Werner change the bed, his face was grey, his shoulders hunched.

An hour later, Werner’s eight-year-old sister, Bettina, pestered him about something. He started yelling, then grabbed Minnie, a beautiful doll with a painted porcelain head and reddish gold hair like his sister’s. He slammed the doll on the floor, hard. Bettina screamed until he stopped. But the damage was done. Minnie’s nose was chipped, her head cracked.

Seeing what had happened, his father raised his hand to smack the boy, then stopped. “Why are you so mean to your sister? She’s done nothing to you!” While Bettina sobbed, Father tried to repair the crack. “See, sweetie, she looks all right now,” he said, handing the doll back. Bettina nodded but Werner could see she was still frightened. What might he break the next time his anger spilled out?

Werner took his sister’s hand. “I won’t be horrid again. Promise.” She tried to smile.

For several days, his father barely spoke to him. He seemed deep in thought. Finally, he said, “I am going to take you to the orphanage, Werner. You will be safer there.”

Werner stared at him, shocked. Leave their home? Go to an orphanage? How was that possible?

“Not forever, my son,” Father added, “just for now, I promise.”

When they reached the orphanage, his father told Frau Schutz, “Ever since their mother died, life has been growing harder and harder. I feel that I can no longer keep Werner safe. Maybe if he’s here with other boys, Jewish boys, and a kind woman...” His voice faded at he looked at Frau Shutz.

While they talked, Werner’s head hung low. He stared at the dark, scratched, wooden floor. He had failed his father and hurt his sister. No wonder he was being sent away from home.

The woman had doughy skin, brightened with rouge and lipstick. “I understand.” She put an arm around the boy’s shoulders. “Don’t worry about your son. You do what you must do, that’s how it is nowadays.”

At last Werner was leaving that dreary stone building. Running, then walking, then running again, he barely felt the chilly rain. Two miles into town and then through the town’s streets, past the empty market square and the cathedral with its tall spire. He passed Jewish stores, now shut and boarded up, with big yellow stars painted crudely across the fronts. He didn’t even notice; his mind was on one thing only – home.

Chapter Three

Hit by a strong gust of wind, Werner clutched his thin sweater and shivered. His heart pumped with excitement. Home. Home. Home. He didn’t stop until he reached their small brown house with green shutters. He stared at the dark wooden door. Often, he had dreamed of running away and coming here on his own. But filled with shame and remorse, he had waited for his father to want him there. To ask him home.

Indeed, the door swung open as soon as he knocked. “Werner,” Father murmured, hugging the boy warmly as soon as he stepped inside.

Gazing around the parlor, Werner’s eyes feasted on stuff he knew well. A dumpy green sofa, the faded rose-covered carpet, dusty oil paintings, and a glass-fronted bookcase, overflowing with books. Everything seemed the same except…he spied an empty place on the floor where his mother’s shiny black piano once stood.

“Werner!” Bettina ran up and hugged her brother, her face shining with delight. She held up her doll Minnie for him to kiss, and he gave the doll a big smack on its tiny pink porcelain lips. Bettina laughed aloud.

“You must be hungry,” said Father. “I’ll get you something to eat.” He disappeared into the kitchen. Werner’s heart swelled with pleasure. Finally he was back home again where he belonged. He would be good now, cause no trouble and make his father proud. Whatever evils the family might endure – and they were many – they could face them together as a family.

For a long time, Father had tried to explain away the troubles caused by the Nazis. “This is a difficult time for Germany. People have no work; they’re hungry, desperate. They are blaming the Jews as they always do when times are difficult.”

That’s what he said when he was fired from his job as a math teac

her at a boys school. That’s what he said when they were forbidden to shop in stores owned by Christians. Or ride on the tram or sit in public parks. But when Jews began being hauled out of their houses and beaten up on the streets, or when they disappeared altogether, Father stopped making excuses. Now he sat home all day in a dark room listening to Beethoven and Brahms and Mendelssohn, the German music he so loved.

“Look what I have,” exclaimed Father, rushing back in the room. “Black bread and a pot of herring!”

“Wunderbar, Papa!” Werner grinned. The herring smelled delicious, good and fishy.

“Bettina, set the table, will you?” The girl quickly laid out some dishes and silverware. Werner’s family had never had a lot of things, yet they enjoyed what they had. Friday nights were special – a lace cloth spread on the table, china dishes and a pair of silver candlesticks. Platters of meat and potatoes, rye bread, butter and some sort of delicious cake.

“Ja, ja, very good.” Father rubbed his hands, inspecting the black bread and herring as if it was a banquet.

“It is a very good day,” Werner said. “A splendid day!”

“Here’s a little treat,” Father smiled, going to the cabinet and pulling out a bottle of schnapps and two little glasses. He poured the clear schnapps into each glass and handed one to his son. “Drink up.”

Werner’s eyes widened. Father had never offered him alcohol before. Taking a sip, the sharp liquor burned his throat, though he tried not to wince. Father watched carefully, his smile slowly fading. “You are probably wondering why I asked you to come?”

Forced Journey

Forced Journey